If you’ve ever spent time with Filipinos, you’ve probably heard the words “Tagalog” and “Filipino” used almost interchangeably. For many, the difference feels minor, but behind those two labels is a long history shaped by migration, colonization, nationalism, and modern technology. Understanding the distinction isn’t just about semantics, it’s about how the Philippines defines its national identity, and increasingly, how that identity is represented in digital spaces and an increasingly AI-centric world.

From Austronesian roots to a colonial transformation

To understand Filipino, we start with its base: Tagalog. As part of the Austronesian language family, Tagalog is related to Indonesian, Malay, and many languages across Southeast Asia and the Pacific. Its story traces back more than 4,000 years to Proto-Austronesian communities in Taiwan.

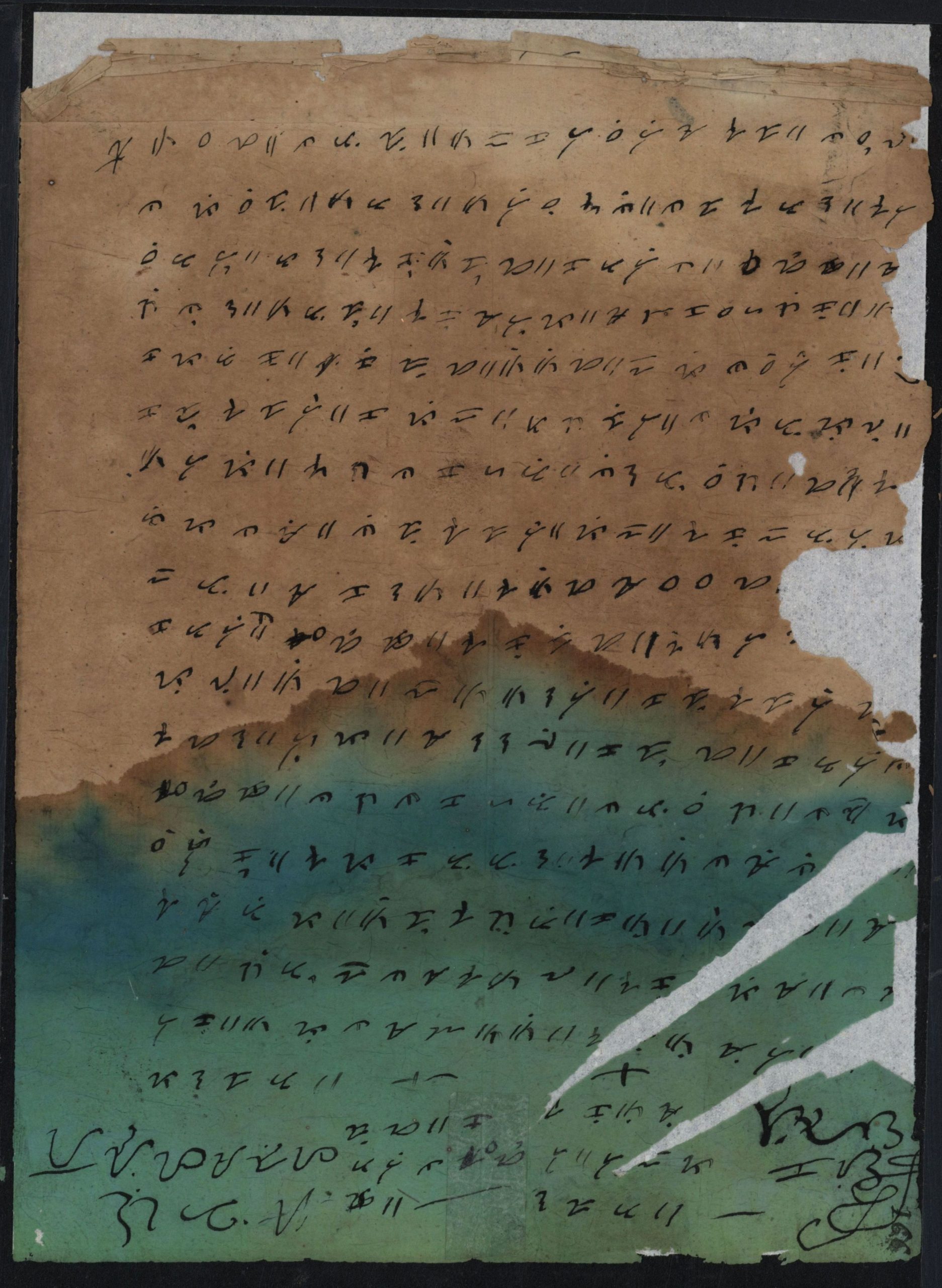

Long before the Spaniards arrived in the 16th century, Tagalog was already the main language of Central and Southern Luzon. Continuous trade with Chinese, Indian, and Southeast Asian cultures enriched the vocabulary and ideas embedded in the language. At the time, the Tagalogs used the indigenous Baybayin script for personal communication, poetry, and short messages, while longer histories and epics were preserved through a rich oral tradition.

Fig 1. An example of the pre-colonial Baybayin script.

Spanish colonization (1565-1898) systematically sidelined Baybayin, but distinctively, it colonized the script without replacing the tongue. As the friars prioritized evangelization over assimilation, they used the Latin alphabet to translate religious texts into local dialects rather than teaching Spanish to the masses. With official documents and church texts shifting to Latin-based Tagalog—and the Latin script proving more practical for new Spanish-influenced sounds—Baybayin quickly lost relevance and faded from use.

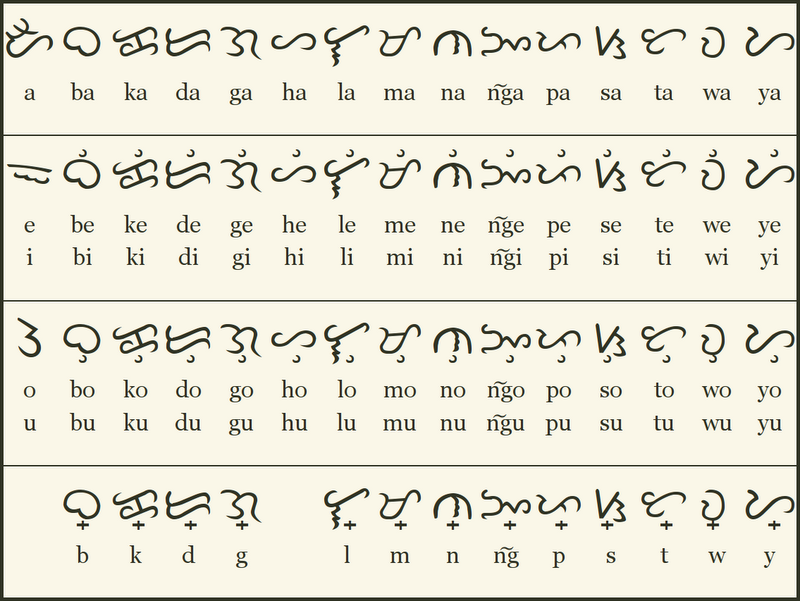

Fig 2. A female Thomasite teacher instructing Filipino students

Following the Spanish-American War in 1898 up until the end of the American occupation in 1946, the United States utilized a radically different strategy: assimilation through mass education. Unlike the exclusive nature of Spanish rule, the Americans established a public schooling system through Act No. 704 of 1901, that enforced English as the sole medium of instruction. By making English the new entry point for commerce and bureaucracy, the Americans effectively institutionalized a foreign language in mere decades, reshaping the linguistic landscape far more aggressively than Spain and pushing Tagalog into a new role during the rise of nationalism.

Constructing a national language

The dream of a unified Filipino nation has always been deeply tied to the dream of a single national language. In 1937, President Manuel L. Quezon declared Tagalog as the basis for the national language. This decision was driven by a mix of commercial practicality and political dominance. As the language of the capital, Tagalog had long served as the default medium for trade. However, it also reflected the influence of the region’s elite. With the seat of government and the center of the revolution historically situated in the Tagalog regions, the dialect naturally became the language of power (refer to the revolutionary constitution).

But in a country home to over 175 distinct languages, this decision was met with controversy. Speakers of Cebuano, Ilocano, and other major languages, felt excluded, sparking a debate about “Tagalog imperialism“—a dynamic which can be likened to the elevation of the Beijing dialect to Standard Mandarin in unifying 20th century China.

To create a more inclusive national language, the term “Pilipino” was introduced in 1959. But it wasn’t until the 1987 Constitution that “Filipino” became the official national language, mandating that it be developed and enriched by all Philippine languages. This mandate represented a big conceptual leap. The 1987 Constitution imagined Filipino as an inclusive national language drawing from all Philippine languages, but the reality is that Filipino remains fundamentally Tagalog; its grammar, syntax, and core vocabulary are still Tagalog at their base, even as it absorbs words from other languages.

Does ‘Filipino’ represent all Filipinos?

Today, the linguistic environment is complex. While Filipino is the national language, is it spoken everywhere? Yes and no. Thanks to mass media and the education system, almost all Filipinos understand it. However, in regions like Visayas and Mindanao (⅔ of the major islands of the Philippines), it often serves as a lingua franca for speaking with outsiders (i.e. business), whereas the local vernacular dominates daily life.

Fig 3. A map showing the linguistic complexity of the Philippine archipelago.

In fact, resentment toward the centralization of Tagalog persists. In areas where Cebuano (part of the Bisaya languages) is dominant, pushback against “Imperial Manila” remains tangible, with some locals preferring to use English rather than Filipino in formal settings. This friction has even migrated to digital spaces, where the viral “Tagalog vs. Bisaya” meme trend frequently resurfaces these long-standing regional rivalries.

This linguistic tension has found new life online, where language itself is evolving faster than ever. Social media has become a laboratory for linguistic evolution: Gen Z slang like charot (just kidding) and sana all (wish it was like that for everyone) among others spread virally across platforms. Tiktok, Twitter/X, and Facebook comments sections show Filipino absorbing not just English loan words, but internet-native expressions that would make purists wince. These digital spaces are where the “development and enrichment” mandated by the constitution actually happens—not in government committees, but through millions of Filipinos creating language in real-time.

Furthermore, the Philippine linguistic ecosystem outside the capital is fragile. While major regional languages (like Ilocano, Hiligaynon, Bikolano, etc.) remain robust, the pressure of learning Filipino and English is impacting smaller languages. Dozens of indigenous languages, such as those spoken by the Itneg and Batak communities are currently classified as dying or endangered as younger generations shift away from them due to the cultural and economic hegemony of the two national languages.

Tagalog vs Filipino: What’s the actual difference?

In practice, linguists generally agree on this:

Filipino = the standardized, modern, national-language variety of Tagalog.

Structurally, they share the same grammar. The difference lies in:

1. Vocabulary breadth

Filipino absorbs words not only from Tagalog, but also Cebuano, Ilocano, Spanish, English, and more.

-

Katarungan (Justice) - adopted from the Bisaya root tarong (straight/right), used interchangeably with the Spanish-derived hustisya

-

Trabaho (Work) - a loan word from the Spanish word: trabajo

-

Kompyuter (Computer) - a loan word ‘Filipinized’ from the English word: computer

2. Alphabet expansion

-

Baybayin: 17 characters

-

Abakada (Tagalog): 20 letters

-

Modern Filipino: 28 letters; adding F, J, Ñ, Z, among others, to accommodate a wider range of words

3. Everyday usage

Modern Filipino reflects how people actually speak today, full of code-switching between Filipino, English, and regional languages.

Examples:

-

Mag-picture tayo. (Let’s take a picture together.) [Filipino+English]

-

Na-late ako sa work dahil sa traffic. (I was late for work because of traffic.) [Filipino+English]

-

I am going to the market, bibili lang ako ng pagkain, para naay makaon sa balay. (I am going to the market, I will just buy some food, so there is something to eat at home.) [Filipino+English+Cebuano]

For many Filipinos, especially in urban areas, this trilingual juggling act is the norm. A Cebuano speaker in Manila might switch between Cebuano with family, Filipino with colleagues, English in formal emails, and a fluid mix of all three when texting friends. For NLP, this means our “Filipino” data isn’t just Tagalog with borrowed words, it’s a dynamic ecosystem where boundaries between languages blur constantly.

Why this matters for NLP

For NLP researchers, the distinction between Tagalog and Filipino isn’t about grammar as structurally, they follow the same system. What matters is knowing what our data actually contains.

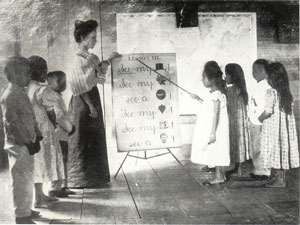

Most online Philippine text, whether scraped in Common Crawl or a dataset on HuggingFace—uses the ISO code tl (Tagalog). But the actual content inside is overwhelmingly Filipino, the modern, evolving variety that naturally encompasses code-switching and usage of loan words.

Fig 4. A standard dataset card showing the language code ‘tl’ (Tagalog) but labeled Filipino

In practice, this means we’re already working with Filipino, even though the metadata in data cards, language tags in model configurations, and standard ISO codes are universally labeled “Tagalog” (tl). We don’t need to change the ISO standard or relabel existing corpora. What’s important is recognizing the distinction so that we understand the linguistic reality behind the data we use.

Filipino as a linguistic bridge

Just as Indonesian serves as an anchor for regional languages like Javanese or Sundanese, Filipino can serve as the pivot language for Philippine NLP. Because it shares core grammar and cognates with Cebuano, Hiligaynon, Waray, Kapampangan, Bikol, and many others, a strong Filipino model creates a foundation that accelerates progress for every other language in the country.

| English | Tagalog (Pivot) | Cebuano | Ilocano | Kapampangan |

| :— | :— | :— | :— | :— |

| Eye | Mata | Mata | Mata | Mata |

| Two | Dalawa | Duha | Dua | Adwa |

| House | Bahay | Balay | Balay | Bale |

| New | Bago | Bag-o | Baro | Bayu |

Fig 5. A lexical comparison showing high similarity (cognates) across major Philippine languages.

This allows researchers to utilize transfer learning, by effectively “recycling” what an AI learns from the data rich Filipino language and applying it to regional languages that have less data. Instead of building models from scratch for every dialect and language, a good Filipino system can accelerate the creation of translation tools and datasets for the rest of the archipelago.

Understanding the Tagalog-Filipino distinction helps us build models that reflect how people actually communicate today, without needing to replace existing standards.

The double-edged sword: Progress and preservation

Here’s the cold truth: as we build better Filipino NLP models, we might be accelerating the very problem we hoped to solve. With every successful Filipino chatbot, translation tool, or voice assistant, we reinforce Filipino’s dominance, creating economic incentives/dependencies which push communities away from their local languages.

But the same technology could be their lifeline. If Filipino serves as a true pivot language, transfer learning makes it economically feasible to build tools for languages with tiny datasets. Imagine a Filipino to Itneg translation model helping grandparents connect with their apo’s who never learned the language, or documentation systems preserving Batak oral traditions before the last fluent speakers pass away.

Fig 6. The San Juanico Bridge spans the strait between Samar and Leyte—a symbol of connection in an archipelago of over 7,600 islands.

The choice isn’t inevitable. It depends on whether researchers treat Filipino as the destination or as the bridge. If we stop at building excellent Filipino models, we’ve simply digitized linguistic hegemony. But if we use Filipino’s advantage to pull smaller languages into the digital age, we might preserve what otherwise would be lost.

Preserving identity in the algorithm

The difference between Tagalog and Filipino isn’t just academic trivia—it reflects how the Philippines defines itself as a nation. Acknowledging Filipino as the national, standardized, evolving language means acknowledging our linguistic diversity while recognizing that its structure remains inherently rooted in Tagalog.

For NLP researchers, this awareness shapes everything we build. It helps us interpret our data honestly, design models that reflect how Filipinos actually communicate, and most critically, ensures that as we bring Philippine languages into the age of AI, we’re creating tools that connect rather than divide.

The algorithms we create today will shape which languages survive tomorrow. That’s not just a technical challenge, it’s a responsibility to the 175+ languages that make up who we are.